Chan Gunn, MD, is a Clinical Professor at the Multidisciplinary Pain Center at the University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, Washington. Dr. Gunn describes three categories of pain, which are quite useful for the following discussion (1). These three categories are:

1)Nociception Pain

In this category of pain, there is no tissue damage, and therefore no inflammation. This is the type of pain one would experience if someone stepped on your toe; one would have pain but no tissue damage or inflammation. This type of pain does not require a healthcare provider to diagnose the cause of the pain. The cause of the pain is obvious: someone is standing on your toe.

Likewise, this type of pain does not require healthcare provider treatment. The treatment is obvious: get the person’s foot off your toe. The patient self-treats.

With this type of pain, once the person’s foot is off your toe, you experience immediate and lasting relief. The prognosis is excellent.

This is the type of pain that most patients (and insurance companies) hope they are experiencing, hoping for instant relief. Sadly, this type of pain rarely makes it into a doctor’s office because it is self-diagnosed and treated.

2)Algogenic or Inflammatory Pain

Instead of someone stepping on your toe, they smacked your toe with a hammer. Even though the hammer is no longer actually on your toe, your toe still hurts. The hammer added something to the equation: trauma, tissue damage, and inflammation. This disruption of the tissues and blood vessels by the trauma produces and releases inflammatory chemicals that are often collectively called algogenic exudates.

The inflammatory algogenic chemicals alter the thresholds of the nociceptive afferent system, increasing the pain electrical signal to the brain. Instant relief for this type of pain is not possible. The pain subsides as inflammation resolves and the nociceptive afferents system becomes sub-threshold.

Individuals suffering from this type of pain often go to healthcare providers for relief. Treatment often involves anti-inflammatory efforts (controlled motion, drugs, omega-3s, ice, electrical modalities, low–level laser therapy, etc.) and efforts to accelerate healing (low-level laser therapy). Depending upon the degree of tissue injury and a myriad of individual unique characteristics, response can last days, week, or months.

Importantly, for the chiropractic profession, there is credible evidence that mechanically-based interventions, including spinal adjusting, can disperse the accumulation of inflammatory chemicals, reducing that person’s pain. This is particularly well documented when the source of the pain is the patient’s intervertebral disc (2).

Since the intervertebral disc is avascular, only improved motion can disperse the inflammatory chemicals. Spinal adjusting improves spinal motion, and improved spinal motion disperses the accumulation of the inflammatory chemicals. This model was profiled by Vert Mooney, MD, in his Presidential Address International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine (2). Dr. Mooney states:

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

“The fluid content of the disk can be changed by mechanical activity.”

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration [in the disc].”

“Research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually, the human intervertebral disk lives because of movement.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disk. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

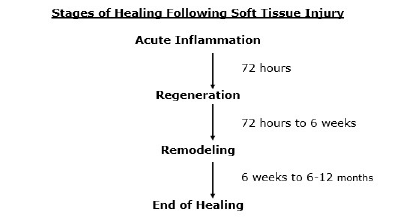

As noted with the hammer analogy, inflammatory pain subsides as the injured tissues heal. Without controversy, injured tissues heal in three distinct steps, as follows (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8):

Once again, quite important to the chiropractic profession and their patients, these phases of healing and the concomitant pain are greatly benefited from controlled motion (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18). This would include chiropractic adjusting (19, 20, 21).

3)Neuropathic Pain

This category of pain is pain caused from injury and damage of the nerve itself. Neuropathic pain has the potential to become chronic and debilitating. Neuropathic pain affects approximately 3–17% of the chronic pain population in the world (22).

Important for this discussion, neuropathic pain includes compressive neuropathology.

Compressive Neuropathology

Compressive neuropathology:

- Peripheral compressive neuropathology, also known as compressive neuropathy.

An example of compressive neuropathy is carpal tunnel syndrome. The median nerve is compressed at the wrist.

- Nerve root compressive neuropathology, also known as compressive radiculopathy.

Between every spinal segmental level there is a spinal nerve root.

In compressive radiculopathy, the spinal nerve root is compressed at the level of exit from the spinal column.

In the neck, the spinal nerve root extends down the shoulder and into the arm(s).

In the low back, the spinal root extends down the pelvis and into the leg(s).

When a spinal nerve root is compressed (radiculopathy), it generates symptoms (pain, numbness, tingling, hypersensitivity, burning, achiness, etc.) and/or functional disturbances (weakness, atrophy, etc.) in the arm(s) and/or leg(s).

Compressive radiculopathy is the most concerning clinical syndrome seen in chiropractic clinical practice. This is because excessive or prolonged compression may lead to death of some of the nerve fibers resulting in permanent functional impairments. The most common cause of nerve root compression is herniation of the intervertebral disc.

Spinal manipulation and chiropractic care have a long history in the management of discogenic compressive radiculopathy. However, these patients often require longer treatment duration and more frequent chiropractic visits. To understand the magnitude of the compression, chiropractors often make use of diagnostic imaging, such as x-rays, MRI, CT, etc.

Statistically, compressive radiculopathy is rare, being found in less than 10% of chiropractic clinical practice patients (20). Sometimes, patients suffering from compressive radiculopathy will require a surgical decompression. Chiropractors are trained to monitor patient progress for any symptoms or signs that might benefit from or require a surgical consultation.

Review of Selected Studies

For decades, numerous studies have shown that spinal adjusting is appropriate and usually successful in the management of compressive radiculopathy.

In 1954, an article was published in the Instructional Course Lectures of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, titled (23):

Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions

The author states:

“From what is known about the pathology of lumbar disk lesions, it would seem that the ideal form of conservative treatment would theoretically be a manipulative closed reduction of the displaced disk material.”

“Many forms of manipulation are carried out by orthopaedic surgeons and by cultists and this form of treatment will probably always be a controversial one.”

In 1969, a study was published in the British Medical Journal, titled (24):

Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation

The patients in this study presented with an acute onset of low back and buttock pain that did not respond to rest. Diagnostic epidurography showed a clinically relevant small disc protrusion, along with antalgia and positive lumbar spine nerve stretch tests. These patients were then treated with rotation manipulations of the lumbar spine, accompanied with a thrust maneuver. The manipulations were repeated until abnormal symptoms and signs had disappeared. Following the manipulations there was resolution of signs, symptoms, antalgia, and reduction in the size of the protrusions. The authors state:

“Rotation manipulations apply torsion stress throughout the lumbar spine. If the posterior longitudinal ligament and the annulus fibrosus are intact, some of this torsion force would tend to exert a centripetal force, reducing prolapsed or bulging disc material.”

“The results of this study suggest that small disc protrusions were present in patients presenting with lumbago and that the protrusions were diminished in size when their symptoms had been relieved by manipulations.”

Also, in 1969, a study was published in the Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, titled (25):

Low Back Pain and Pain Resulting

from Lumbar Spine Conditions:

A Comparison of Treatment Results

The author compared the effectiveness of heat/massage/exercise to spinal manipulation in the treatment of 184 patients that were grouped according to the presentation of back and leg pain. The further the sciatic pain radiated down the leg, the greater the benefit of spinal manipulation. This study was reviewed in the 1990 book, Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, which stated (26):

“A well-designed, well executed, and well-analyzed study.”

In the group with central low back pain only, “the results were acceptable in 83% for both treatments. However, they were achieved with spinal manipulation using about one-half the number of treatments that were needed for heat, massage, and exercise.”

In the group with pain radiating into the buttock, “the results were slightly better with manipulation, and again they were achieved with about half as many treatments.”

In the groups with pain radiation to the knee and/or to the foot, “the manipulation therapy was statistically significantly better,” and in the group with pain radiating to the foot, “the manipulative therapy is significantly better.”

“This study certainly supports the efficacy of spinal manipulative therapy in comparison with heat, massage, and exercise. The results (80–95% satisfactory) are impressive in comparison with any form of therapy.”

In 1977, the third edition of Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications was published. This reference book includes a section pertaining to the protruded disc with compressive radiculopathy, titled (27):

“Treatment of Intervertebral Disc Herniation with Manipulation”

“Some orthopaedic surgeons practice manipulation in an effort at repositioning the disc. This treatment is regarded as controversial and a form of quackery by many men. However, the author has attempted the maneuver in patients who did not respond to bed rest and were regarded as candidates for surgery. Occasionally, the results were dramatic.”

In 1987, a study was published in the journal Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research, titled (28):

Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation

This study involved 517 patients with protruded lumbar discs with compressive radiculopathy who were treated with manipulation. Eighty-four percent of the patients achieved a successful outcome and only 9% did not respond. The authors stated:

“Manipulation of the spine can be effective treatment for lumbar disc protrusions.”

“Most protruded discs may be manipulated.”

“Gapping of the disc on bending and rotation may create a condition favorable for the possible reentry of the protruded disc into the intervertebral cavity, or the rotary manipulation may cause the protruded disc to shift away from pressing on the nerve root.”

In 1989, a study was published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, titled (29):

Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Herniation:

Treatment by Rotational Manipulation

This was a case study of a patient with an “enormous central herniation lumbar disc” who underwent a course of side posture manipulation. The patient improved considerably with only 2 weeks of treatment. The authors state:

“It is emphasized that manipulation has been shown to be an effective treatment for some patients with lumbar disc herniations.”

In 1993, a “Review of the Literature” was published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, titled (30):

Side Posture Manipulation for Lumbar Intervertebral Disk Herniation

The authors state:

“The treatment of lumbar disk herniation by side posture manipulation is not new and has been advocated by both chiropractors and medical manipulators.”

“The treatment of lumbar intervertebral disk herniation by side posture manipulation is both safe and effective.”

In 1995, a study was published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, titled (31):

A Series of Consecutive Cases of Low Back Pain

with Radiating Leg Pain Treated by Chiropractors

The authors retrospectively reviewed the outcomes of 59 consecutive patients complaining of low back and radiating leg pain, and were clinically diagnosed as having a lumbar spine disk herniation with compressive radiculopathy: 90% of these patients reported improvement of their complaint after chiropractic manipulation. The authors state:

“Based on our results, we postulate that a course of non-operative treatment including manipulation may be effective and safe for the treatment of back and radiating leg pain.”

In 2006, a study was published in The Spine Journal, titled (32):

Chiropractic Manipulation in the Treatment

of Acute Back Pain and Sciatica with Disc Protrusion:

A Randomized Double-blind Clinical Trial

of Active and Simulated Spinal Manipulations

The purpose of this study was to assess the short- and long-term effects of spinal manipulations on acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion. It involved 102 patients. The manipulations or simulated manipulations were done 5 days per week by experienced chiropractors for up to a maximum of 20 patient visits, “using a rapid thrust technique.” Re-evaluations were done at 15, 30, 45, 90, and 180 days. The authors state:

“At the end of follow-up a significant difference was present between active and simulated manipulations in the percentage of cases becoming pain-free.”

“Patients receiving active manipulations enjoyed significantly greater relief of local and radiating acute LBP, spent fewer days with moderate-to-severe pain, and consumed fewer drugs for the control of pain.”

“No adverse events were reported.”

In 2010, a study was published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, titled (33):

Manipulation or Microdiskectomy for Sciatica?

A Prospective Randomized Clinical Study

Forty consecutive consenting patients with lumbar disc herniation and radiculopathy who failed at least 3 months of nonoperative management including treatment with analgesics, lifestyle modification, physiotherapy, massage therapy, and/or acupuncture, were randomized to either surgical microdiskectomy or standardized chiropractic spinal manipulation. The authors state:

“Sixty percent of patients with sciatica who had failed other medical management benefited from spinal manipulation to the same degree as if they underwent surgical intervention.... Patients with symptomatic lumbar disk herniation failing medical management should consider spinal manipulation followed by surgery if warranted.”

In 2014, a study was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, titled (34):

Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise with

Advice for Subacute and Chronic Back-Related Leg Pain

This study included 192 patients who were suffering from back-related leg pain for at least 4 weeks. The authors state:

“For leg pain, spinal manipulative therapy plus home exercise and advice had a clinically important advantage over home exercise and advice (difference, 10 percentage points) at 12 weeks.”

“For patients with subacute and chronic back-related leg pain, spinal manipulative therapy in addition to home exercise and advice is a safe and effective conservative treatment approach, resulting in better short-term outcomes than home exercise and advice alone.”

Also in 2014, a study was published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, titled (35):

Outcomes of Acute and Chronic Patients with Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Confirmed Symptomatic Lumbar Disc Herniations Receiving High-Velocity, Low-Amplitude, Spinal Manipulative Therapy

The purpose of this study was to document outcomes of patients with confirmed, symptomatic lumbar disc herniations and compressive radiculopathy that were treated with chiropractic side posture high-velocity, low-amplitude, spinal manipulation to the level of the disc herniation. The authors state:

“The proportion of patients reporting clinically relevant improvement in this current study is surprisingly good, with nearly 70% of patients improved as early as 2 weeks after the start of treatment. By 3 months, this figure was up to 90.5% and then stabilized at 6 months and 1 year.”

“A large percentage of acute and importantly chronic lumbar disc herniation patients treated with chiropractic spinal manipulation reported clinically relevant improvement.”

“Even the chronic patients in this study, with the mean duration of their symptoms being over 450 days, reported significant improvement, although this takes slightly longer.”

“A large percentage of acute and importantly chronic lumbar disc herniation patients treated with high-velocity, low-amplitude side posture spinal manipulative therapy reported clinically relevant ‘improvement’ with no serious adverse events.”

“Spinal Manipulative therapy is a very safe and cost-effective option for treating symptomatic lumbar disc herniation.”

In 2021, a study was published in the American Journal of Medicine titled (36):

Spinal Manipulation for Subacute and Chronic Lumbar Radiculopathy

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of spinal manipulation for the management of subacute and/or chronic lumbar radiculopathy. Forty-four patients, with unilateral radicular low back pain lasting more than 4 weeks, were randomly allocated to a treatment group (manipulation + physiotherapy) and a control group (physiotherapy only). The authors state:

“Spinal manipulation improves the results of physiotherapy over a period of 3 months for patients with subacute or chronic lumbar radiculopathy.”

“Minimum side effects, ease of administration, and patient satisfaction are the expected benefits of manipulation.”

In 2022, a study was published in the BMJ Open, titled (37):

Association Between Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation and Lumbar Discectomy

in Adults with Lumbar Disc Herniation and Radiculopathy

The authors assessed matched cohorts of 5,785 patients with a mean age of 37 years. They note that it is common for patients with lumbar disc herniations and compressive radiculopathy to receive chiropractic care or undergo surgery to remove herniated disc material, a procedure called discectomy. Prior studies have found that patients who initiate care for low back pain with a chiropractor have significantly reduced odds of having discectomy.

In this study, the relative odds for discectomy were significantly reduced in the chiropractic cohort compared with the cohort receiving other care over 1-year (by 69%) and 2-year follow-up (by 77%). This study shows that patients initially receiving chiropractic care for lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy have reduced odds of discectomy over 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

Conclusions

It is understood that some patients suffering from discogenic compressive radiculopathy (neuropathic pain syndrome) will require some form of decompressive spinal surgery. The studies presented here support that prior to surgery, spinal manipulation should be tried in an effort to avoid surgery. Spinal manipulation, especially by those expertly trained (chiropractors), is safe and often very effective. Chiropractors are also trained to monitor patient progress for any symptoms or signs that might benefit from a surgical consultation.

REFERENCES:

- Gunn CC; The Gunn Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain: Intramuscular Stimulation for Myofascial Pain of Radiculopathic Origin; Churchill Livingston; 1996.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; October 1987; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

- Oakes BW; Acute Soft Tissue Injuries; Nature and Management; Australian Family Physician; July 1981; Vol. 10; Supplement 7; pp. 3-16.

- Roy S, Irvin R; Sports Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation; Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1983.

- Frank C, Amiel D, Woo S, Akeson W; Normal ligament Properties and Ligament Healing; Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research; June 1985.

- Kellett J; Acute soft tissue injuries-a review of the literature; Medicine and Science of Sports and Exercise; American College of Sports Medicine; October 1986; Vol. 18; No.5; pp. 489-500.

- Woo S, Buckwalter J; Injury and Repair of the Musculoskeletal Soft Tissues; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1988.

- Cohen IK, Diegelmann RF, Robert F, Lindbald WJ; Wound Healing, Biochemical & Clinical Aspects; WB Saunders; 1992.

- Stearns ML; Studies on development of connective tissue in transparent chambers in rabbit’s ear; American Journal of Anatomy; Vol. 67; 1940; p. 55.

- Cyriax, J; Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions; Bailliere Tindall; Vol. 1; 1982.

- Salter R; Continuous Passive Motion, A Biological Concept for the Healing and Regeneration of Articular Cartilage, Ligaments, and Tendons; From Origination to Research to Clinical Applications; Williams and Wilkins; 1993.

- Buckwalter J; Effects of Early Motion on Healing of Musculoskeletal Tissues; Hand Clinics; Vol. 12; No. 1; February 1996.

- Hildebrand K, Frank C; Scar Formation and Ligament Healing; Canadian Journal of Surgery; December 1998; Vol. 41; No. 6; pp. 425-429.

- Kannus P; Immobilization or Early Mobilization After an Acute Soft-Tissue Injury?; The Physician And Sports Medicine; March, 2000; Vol. 26; No 3; pp. 55-63.

- Hildebrand KA, Gallant-Behm CL, Kydd AS, Hart DA; The Basics of Soft Tissue Healing and General Factors that Influence Such Healing; Sports Medicine Arthroscopic Review September 2005; Vol. 13; No. 3; pp. 136–144.

- Walsh W; Orthopedic Biology and Medicine; Repair and Regeneration of Ligaments, Tendons, and Joint Capsule; Orthopedic Research Laboratory; University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; Humana Press; 2006.

- Schleip R; Fascia; The Tensional Network of the Human Body; The Scientific and Clinical Applications in Manual and Movement Therapy; Churchill Livingstone; 2012.

- Hauser RE, Dolan EE, Phillips HJ, Newlin AC, Moore RE, Woldin BA; Ligament Injury and Healing: A Review of Current Clinical Diagnostics and Therapeutics; The Open Rehabilitation Journal; 2013; No. 6; pp. 1-20.

- Haldeman S; Modern Developments in the Principles and Practice of Chiropractic; Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York; 1980.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Fishgrund JS; Neck Pain; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; 2004.

- van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N; Neuropathic Pain in the General Population: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies; Pain; April 2014; Vol. 155; No. 4; pp. 654–662.

- Ramsey RH; Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; Instructional Course Lectures; Vol. 11; 1954; pp. 118-120.

- Mathews JA and Yates DAH; Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation; British Medical Journal; September 20, 1969; No. 3; pp. 696-697.

- Edwards BC; Low back pain and pain resulting from lumbar spine conditions: a comparison of treatment results; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy; September 1969; Vol. 15; No. 3; pp. 104-110.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second edition; JB Lippincott Company; 1990.

- Turek S; Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications; JB Lippincott Company; 1977; page 1335.

- Kuo PP, Loh ZC; Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation; Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research; February 1987; No. 215; pp. 47-55.

- Quon JA, Cassidy JD, O'Connor SM, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation: treatment by rotational manipulation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; June 1989; Vol. 12; No. 3; pp. 220-227.

- Cassidy JD, Thiel HW, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Side posture manipulation for lumbar intervertebral disk herniation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; February 1993; Vol. 16; No. 2; pp. 96-103.

- Stern PJ, Côté P, Cassidy JD; A series of consecutive cases of low back pain with radiating leg pain treated by chiropractors; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; Jul-Aug 1995; Vol. 18; No. 6; pp. 335-342.

- Santilli V, Beghi E, Finucci S; Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion: A randomized double-blind clinical trial of active and simulated spinal manipulations; The Spine Journal; March-April 2006; Vol. 6; No. 2; pp. 131–137.

- McMorland G, Suter E, Casha S, du Plessis SJ, Hurlbert RJ; Manipulation or Microdiskectomy for Sciatica? A Prospective Randomized Clinical Study; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; October 2010; Vol. 33; No. 8; pp. 576-584.

- Bronfort G, Hondras M, Schulz CA, Evans RL, Long CR, Grimm R; Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise With Advice for Subacute and Chronic Back-Related Leg Pain: A Trial With Adaptive Allocation; Annals of Internal Medicine; September 16, 2014; Vol. 161; No. 6; pp. 381-391.

- Leemann S, Peterson CK, Schmid C, Anklin B, Humphreys BK; Outcomes of Acute and Chronic Patients with Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Confirmed Symptomatic Lumbar Disc Herniations Receiving High-Velocity, Low Amplitude, Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study with One-Year Follow-Up; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March/April 2014; Vol. 37; No. 3; pp. 155-163.

- Ghasabmahaleh SH, Rezasoltani Z, Dadarkhah A, Hamidipanah S, Mofrad RK, Sharif Najafi S; Spinal Manipulation for Subacute and Chronic Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial; The American Journal of Medicine; January 2021; Vol. 134; No. 1; pp. 135−141.

- Trager RJ, Daniels CJ, Perez JA, Casselberry RM, Dusek JA: Association Between Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation and Lumbar Discectomy in Adults with Lumbar Disc Herniation and Radiculopathy: Retrospective Cohort Study Using United States’ Data; BMJ Open; December 16, 2022; Vol. 12; No. 12; Article e068262.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”